On the arrival of the s.s Waratah in Melbourne at Victoria dock on the 18th of January 1908, the ship was met by a brave reporter who had been alerted from Adelaide that some passengers had taken legal action against the Lund Line for the poor and unsanitary conditions as well as the overcrowding they had to endure. The reporter went fore and aft eager to try and interview as many passengers as possible. A spokesman for the passengers said we were induced to book on this ship owing to the glowing advertisements inserted in the English newspapers. The steamer has only first and third class accommodation, and it was persistently stated that its "thirds" (cabins) were equal to "seconds" on any ordinary liner. She could comfortably carry 130 passengers in first class saloons, and 300 in her third class compartments. For that number the space allotted to in cabins and public rooms, and saloons is on a GENEROUS SCALE, but what is ample for those people is insanitary and suffocating for 700 or more. The company may not have expected such a rush of passengers, which included many emigrants assisted by the New South Wales Government, but whether they did or not doesn't matter. They accepted double the number they had accommodation and provisions for-pocketing the extra fares, which amount to 17 pounds apiece, with the result we suffered. After we were out two or three days we found the food supply insufficient.

The stewards were also few in number, this occasioning inattention and lack of supervision. A deputation confronted Captain Ilbery and he tried to do the best he could. Some stowaways were discovered and a number of them were pressed into service as stewards, whilst passengers who would lend a hand were promised 2 pounds reward on arrival in Sydney,(they refused the offer, in my new book I deal with this in full). The water was doled out very sparingly, the tea and coffee were very indifferent. Owing to the inadequate flushing the urinal closets (toilet bowls) got into a terrible condition by the time we reached Capetown. The food supply was not good, and the sugar ran out, the puddings were unsweetened, as was the undrinkable tea. Fresh meat was a rarity, and greasy water was served up as soup. As to sleeping, ten men were huddled up in a space 10feet x 10feet x 8feet. There were no portholes in many of the compartments, and when crossing the line (Equator) the heat and discomfort endured was very great. Owing to the want of sufficient flushing water closets and urinals many men utilised one of the coal bunkers for the call of nature, but ultimately the coal bunker was eventually cleared out, and the erstwhile impromptu lavatory was converted to a dining room. Those poor trimmers were shovelling more than coal. As regards bathrooms, only doubtful water was supplied, and people could actually see the bathers from the top deck.

There were many women and children on board including about 30 girls who were being indented as domestic helps, over them was a deplorable want of supervision. In the stern there was an ill-ventilated compartment dubbed an "isolation hospital", its only ventilation was two port holes, one man died there during the voyage. (There were other deaths on board which I have included in my book with the official log book entries in connection with them), another man was on board the crowded ship was in the last stages of consumption. As regards the smokeroom, it was often unbearably crowded. It won't hold more than a couple of dozen, if comfort is studied, but sometimes there were fifty jammed into it. At the bar men were drunk and the permanent saloon often became a rowdy tap room,(PUB). The presence of women and children was totally disregarded by those who used bad language while "under the influence". Concerts were held occasionally, but there was not room for half the passengers. We do not blame the captain or his officers, who did the best they could under the circumstances. It is the shipping company we blame, who for the sake of a few hundred pounds in extra fares treated at least 750 people as we assert. Such is the substance of the complaints made by the third class passengers. The discomforts suffered are proverbial, and in an overcrowded vessel such sufferings must be intensified. The authorities upon board ship look upon the whole genus of passengers as born growlers, but in this case the passengers think they have a reason to growl.

The plucky reporter gave publicity to the growl, as he was duty bound in the public interest, and leaves the statement for the consideration of his readers. While on board he inspected portions of the ship complained of, and what he saw as to accommodation and overcrowding fully bore out the passengers statements. The passengers were limited to a justifiable compliment, but under the extraordinary conditions on which the Waratah was permitted to make her maiden voyage the large dining room' had an adjunct the unsavoury coal bunker, (spar deck,) and the smoking room was a diminutive farce. An inspection of the closets and urinals showed them to be in a dirty condition , as alleged. The question suggests itself: is there no supervising authority in England to see steamers are not allowed to be overcrowd in such a shocking way, and inflict discomfort on the unfortunate passengers, besides, perhaps endangering life in the case of a disaster? The Board of Trade was the responsible authority and their servant Captain Clarke passed the ship as a suitable emigrant ship just as he passed the lifeboats as fit for service for the maiden voyage.

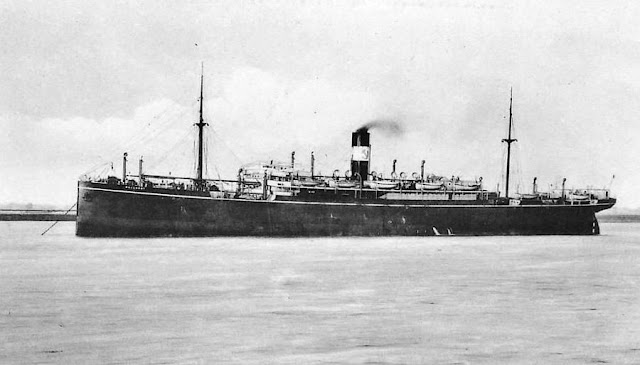

s.s. Waratah.

No room for deck chairs with these 3rd class emigrants.